STEVE HOLE tells the story of an all-but-forgotten, but very accomplished East Sussex-based kitcar manufacturer called S&J Motor Engineers.

Another all-but forgotten eighties kitcar manufacturer that is well worth remembering was S&J Motor Engineers. I have read so much garbage about this company over the years, which always make me laugh.

The man behind the company was the multi-talented engineer Simon Hilton. As far as I know he wasn’t Australian, because he was born in England but it is true that his family moved to Australia when Simon was very young in 1950.

He spent his childhood and formative years there and definitely learnt all about woodwork and became a carpenter. At one stage, he was involved At some stage he also learnt about polymer technology.

Now, I must admit I didn’t really know what this actually meant so I asked Wikipedia, so obviously the following must be true!

According to the gospel according to Wiki, polymer technology is a field of engineering focused on the design, production, and application of polymers, which are large molecules made up of repeating sub-units called monomers. This technology plays a crucial role in various industries, including plastics, textiles, and electronics.

Key Aspects of Polymer Technology

Types of Polymers

Thermoplastics: Can be reshaped when heated and are often recyclable. Examples include polyethylene and polypropylene.

Thermosets: Harden permanently after being shaped and cannot be remelted. Common examples are epoxy and phenolic resins.

Applications

Polymer technology is used in a wide range of applications, such as:

Packaging: Films, bottles, and containers.

Textiles: Clothing and sportswear made from polyester and nylon.

Electronics: Components like circuit boards and insulation materials.

Biomedical: Development of biomaterials for medical devices and drug delivery systems.

Importance of Polymer Technology

The field is essential for creating materials that meet specific performance criteria, such as durability, flexibility, and resistance to environmental factors. It also addresses sustainability challenges by developing biodegradable polymers and recycling methods to reduce plastic waste.

Overall, polymer technology is integral to modern manufacturing and product development, influencing everyday life through various consumer goods and industrial applications.

So, that’s cleared that up! Anyway, I think, in Simon’s case he was a bit of a pioneer in Australia of this technology in relation to dentistry.

Your dentist has several applications where polymers are used including dental adhesives, restorative materials and antimicrobial coatings to improve the longevity and effectiveness of dental treatments.

I also believe that this is why I have seen Simon Hilton described as a dentist.

Not sure how he found time to do it but the Hiltons also founded and ran a very successful classic car sales business in Australia, a top-end operation that regular bought and sold Bugattis and Lagondas as well as various classic Alfa Romeos.

At one stage, Simon was also involved with the production of PVC foam, which was used in items such as lie-jackets.

When he returned to the UK in the late seventies he pursued his love of woodworking and he and wife Joan set up a business in East Sussex making four-poster beds. They had a workshop on the A21 in Hurst Green.

He is still well-regarded for the quality of his four-posters.

He was also a keen car enthusiast with a passion for all things Alfa Romeo. Like lots of people he’d noticed the fact that Italian manufacturers such as Alfa were suffering from rust problems in their cars, which was causing problems.

Simon had always fancied building his own car and when he became aware that mechanically sound models like the GTV were being written off due to affliction by the dreaded tin-worm he based his first car, the Milano on the GTV.

The Hiltons, trading as S&J Motor Engineers were initially based from their home in Victoria Road in Bexhill-on-Sea before they moved to a much bigger house with a large workshop on site within its grounds, in Powdermill Lane in Battle, which links the town to Bexhill-on-Sea.

As I always like to bring a bit of background and history, even trivia to my features, let’s quickly talk about Battle’s conection to the Gunpowder Plot. Known for Battle Abbey and its 1066 conncetions and is a major tourist attraction, it was also once known as The Gunpowder Capital.

In the 17th century there was a roaring gunpowder trade in Batle with the largest ‘manufacturer’ located on what later became the Powdermills Country House Hotel (that was built in about 1850) which is still open to this day.

Plenty of conjecture abounds about which of the many gunpowder producing areas of southern England (a large one in Godstone, Surrey, another in Tunbridge Wells and also Blackboys near Uckfield, East Sussex) although many believe that 35-year old Guido ‘Guy’ Fawkes obtained his gunpowder from Powdermill Lane, battle for his plot to blow up the Houses of Parliament on Novermber 5, 1605.

Even though the Gunpowder Plot failed, word got around that Batle was involved and the area gained a certain notoriety, as a result.

Production continued apace although there were plenty of accidents with over-cooked gunpowder exploding and causing mayhem to buildings and life and limb. One of the most infamous occurred in 1798 when fifteen tonnes of gunpowder was left in the oven too long by a hapless worker and a huge explosion resulted.

Maybe workers were too cavailier with it not understanding fully how dangerous making gunpowder is. Safty gear was almost non-existent and the workers only had leather aprons and clogs with copper soles to prevent sparks, which did little to help them if an acccident happened.

In the end, the chap in charge of issuing licenses to gunpowder mills, the Duke of Cleveland revoked Powdermill Lane’s license to produce the stuff and although the industry continued in Battle it was much diminshed.

Even when in full flow none of the southern England gunpowder producers got near the scale of Waltham Abbey in Essex, which was hugem right up to and including the Crimean and Boer wars.

MILANO

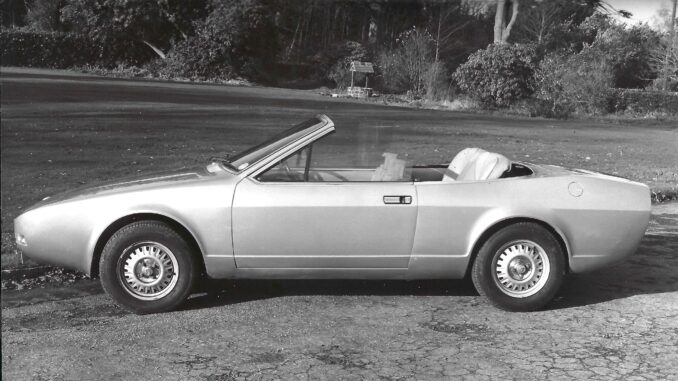

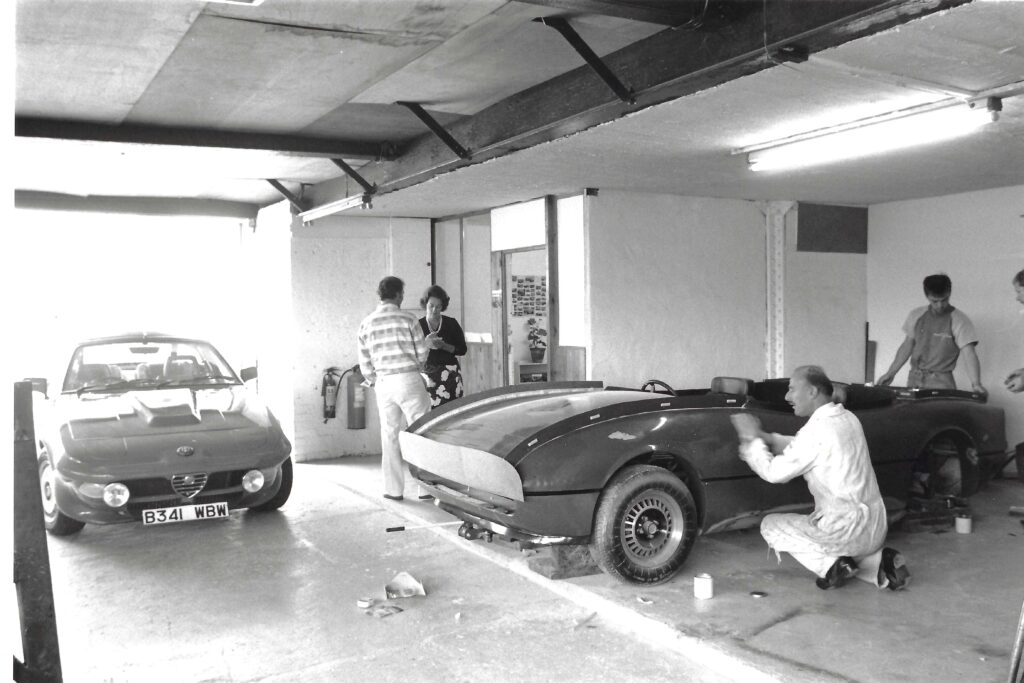

Anyway, back to Simon Hilton and originally, what became known as the Milano (from 1984) was produced as a part-time venture (it had been under development for about four years) while he was still making four-posters, although it did well enough that it became a full-time occupation, with around eight staff employed.

The car was underpinned by a multi-tubular 1.5in box-section, cross-braced ladderframe chassis. Customers were required to use stuff like dashboard, front bulkhead from the GTV donor. The doors were also used but they were shortened and re-skinned for Milano purposes.

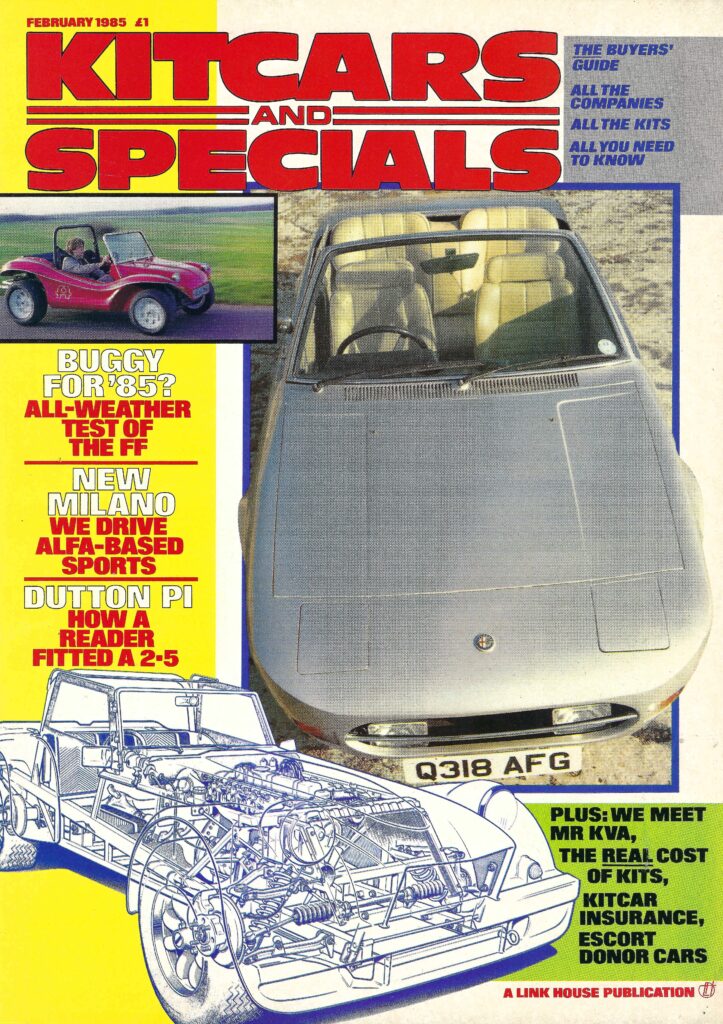

Simon was inspired by Pininfarina’s XJS Spyder concept of 1980. Although I have heard it described as a challenging build, the Milano was an elegant and pretty car. Various Alfa engines (from the GTV range) were possible such as 1800cc (120bhp), 2-litre (130bhp), 2.5-litre V6 (158bhp) or the 3-litre V6 (183bhp). I’d estimate that about 40 Milanos were sold. Ironically, going from being virtually value-less when Simon was making Milanos, a decent Alfetta GTV will probably cost you around £20,000, depending on model and condition.

SPORTIVA

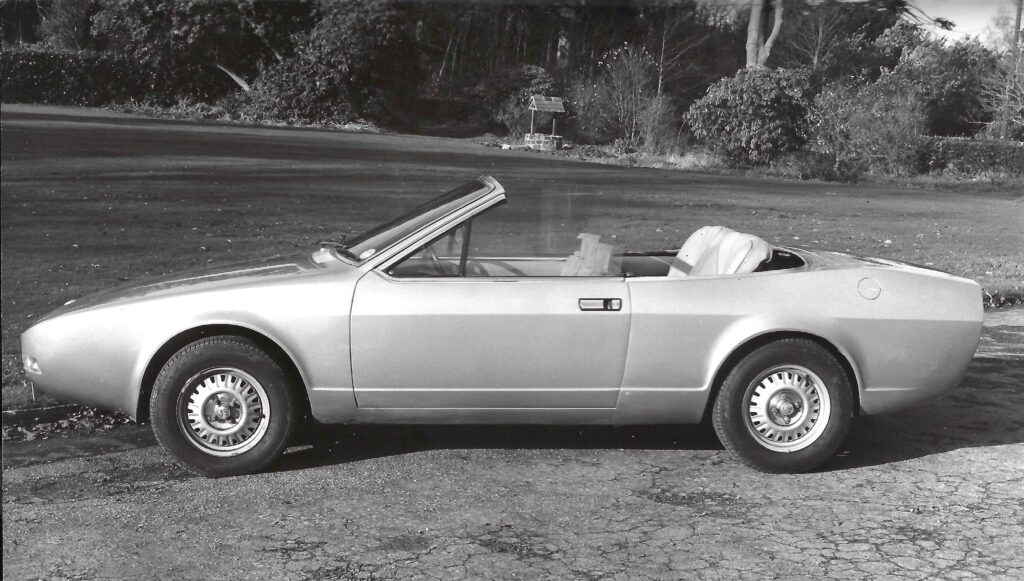

I think Simon was keen to add a second model to his range while he wanted something more sophistocated than the Milano but easier to build. I remember talking to Simon in 1986 soon after he’d launched the Sportiva and he reckoned that it was a much superior car in every way.

Again Alfa Romeo-based, but this time on the beefier Alfetta saloon, the Sportiva had a 1.25in square-tube, 14swg ladderframe chassis, a beautifully triangulated affair.

The Alfetta introduced a new drivetrain layout to Alfa Romeo. The clutch and transmission were housed at the rear of the car, together with the differential for a more balanced weight distribution, as used on the Alfetta 158/159 Grand Prix cars. The suspension featured double wishbones and torsion bars at the front and a de Dion tube at the rear.

The Sportiva kept the same basic architecture with the transaxle and clutch solidly mounted at the rear of the car and Simon always reckoned that the twin-cam 2-litre was the best (about 122bhp) and most flexible unit to use although his demo car had an Autodelta-tuned (they are Alfa Romeo’s famous tuning division) 2-litre version which was fitted to the GTV Delta variant, which even back in 1985 was as rare as hen’s teeth.

This engine had different camshafts, Solex 40 DDHE carburettors and an Autodelta stainless steel exhaust, which may have had its origin with Abarth. A real buzzbomb of an engine it produced 162bhp but went and sounded like it had a lot more.

The Sportiva featured a de Dion rear end, with Alfa wishbones and fabricated in-house parts at the front end. Although Alfetta was prime donor it also pulled parts from other Alfa sources including GTV, Giulietta and even 75. Although well-received the Sportiva didn’t catch on and only around five were sold.

S&J ceased production in 1988 when Simon and Joan returned Down Under although something is nagging my mind that they went to New Zealand, although I might be incorrect and it may well have been Australia.

Out of the blue one day in 1999, a phone call from a chap in Birmingham who ran a media blasting company said that he’d obtained the Sportiva moulds (not the Milano ones) and that he was going to be putting the car back into production ‘very soon’. he talked about changing the donor vehicle but that was the first and last time anything was heard about his plan.